The Model 1871 Ward-Burton bolt action design came at a time when the US military was forward- thinking in its search for a modern arm to adopt as standard issue. At the close of the Civil War, the successful employment of breechloading arms made obvious to even the casual observer that muzzleloading firearms were now obsolete. The demilitarization and reduced funding found in immediate post-war periods limits resources and, therefore, choices in outfitting a military with a weapon that is completely new in both design and fabrication. Not an exception to this general rule, the US military, in 1865, turned to converting its store of muzzleloading muskets, for which they already paid, to breechloaders. Thus began a long line of firearms now commonly known as Springfield “Trapdoor” rifles, named for the hinged breechloading system designed by Erskine S. Allin, a Master Armorer at the Springfield Armory. To their credit, the US Army Ordinance Department only intended the Trapdoor design as a temporary solution and, over the next several years, invited submissions of improved breechloading firearm designs. The search for an advanced military firearm culminated with the 1870-1873 trials that tested proposed designs. Four different models, the Remington patented Rolling Block Model 1870 rifle, the Springfield Model 1870 trapdoor rifle, the Springfield/Sharps Model 1870, and the Ward-Burton Model 1871, were accepted for evaluation in the field and issued to select units, including cavalry, that were stationed out west. Keep in mind that at the time, conflict with western tribes was rampant and the environment as such, provided a rigorous testing environment for these arms.

While the rolling block, trapdoor, and Sharps actions all had external hammers and, therefore, were familiar to the troops, and in the case of the trapdoor and Sharps (falling block) actions, had a significant history of use among the rank and file, the Ward-Burton bolt action design was completely new. Born from a partnership between Bethel Burton and General William G. Ward, the rifle’s concept is considered by many to be the first true bolt action rifle used by the US military (albeit in limited numbers) and far ahead of its time (in fact many features are still standard on bolt action rifles today). Burton, a Brooklyn, NY gunsmith, is credited with an 1859 patent for a bolt action percussion rifle for which he landed a contract from Virginia for 40,000 rifles in 1861 (and then was immediately arrested for conspiring with the Confederacy). After modifying this rifle design to accept brass cartridges in 1868, he met Gen. Ward while exhibiting his bolt action rifle for New York State officials. Upon forming a partnership and, according to one resource, reworking the extractor per Ward’s recommendations, the pair secured a place for both rifles and carbines in the 1870-1873 Field Trials via Gen. Ward’s military connections.

Like the other three firearms models, the Model 1871 Ward-Burton was manufactured in .50-70 Gov’t centerfire (.50-55 for carbines) at the Springfield Armory. Since evaluation was the primary goal, production numbers for Ward-Burton firearms remained low, with a little over 1000 rifles and only about 300 carbines produced – a similar number to the other three models to undergo field trials. With so few made, both Ward-Burton rifles and carbines are considered experimental or trials arms and none were serial numbered.

An advanced design for its day, the extractor, ejector, and firing pin were all integrated into the bolt. Loading proceeds by rotating the bolt handle up (counterclockwise) and pulling back to open the chamber. A round could then be manually inserted (the design did not provide for a magazine well), and the bolt pushed forward, seating the round and cocking the action. Threads at the back of the bolt locked into matching threads in the receiver to secure the bolt, instead of the front lugs found on most modern bolts. After firing, the bolt is once again pulled back, automatically ejecting the spent case and clearing the chamber for the next round to be inserted. Outside of the bolt and receiver, the rest of the firearm and its parts are very much like those of other Springfield arms of the period.

Longitudinal grooves are machined into the bolt body to help prevent problems associated with fouling and dirt buildup. The safety consists of a small, spring-loaded lever and plunger on the rear, right side of the receiver and is activated by pushing the lever forward, with an upward (counterclockwise) rotation. The spring forces the safety pin rearwards and into a hole drilled in the base of the bolt handle, thereby preventing the bolt handle from fully rotating into the firing position. To disengage the safety, the lever is pushed forward and then rotated down (clockwise) to lock it into “fire” position. This allows the bolt handle to sit fully against the stock and engage the trigger.

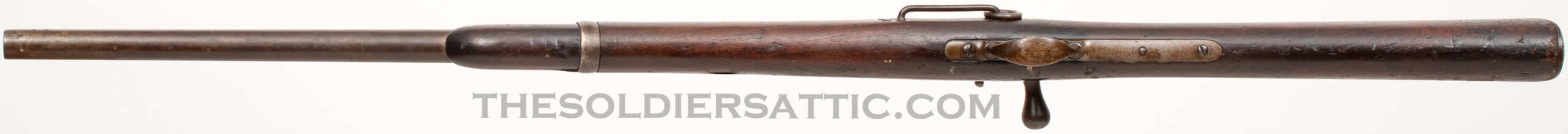

The Model 1871 Ward-Burton carbine has a standard lug front sight with a graduated folding leaf rear sight, saddle ring and bar, standard buttplate, single barrel band, and has no swing-swivels or provision for cleaning rod. The stock is standard Springfield walnut and the 22-inch barrel, iron fittings, and bolt were finished in armory bright. The receiver was casehardened.

Markings include ‘WARD.BURTON.PATENT/DEC. 20. 1859-FEB. 21. 1871’ on top of the bolt, American eagle motif with ‘U.S./SPRINGFIELD 1871’ on the left side of the receiver, and ‘US’ on the upper buttplate tang. On the left side of the stock two cartouches are stamped: one, located in the middle of the saddle ring bar area, reads ‘JWK’, for John W. Keene, inside a banner and the other, located on the wrist just below the bolt handle reads ‘ESA’, for Erskine S. Allin, inside an oval. Just behind the trigger guard on the stock, ‘AL’ is marked into the stock just forward of a box cartouche containing letters that we cannot identify.

Neither the Model 1871 Ward-Burton carbine or rifle fared well during the rigorous field trials. While the failure of some parts occurred, the chief complaint seems to be safety related. Unlike the other three models undergoing the same testing, the Ward-Burton did not have an external hammer that made for easy determination of firing readiness. Nor did the Ward-Burton have any visual way to determine if the firearm was loaded or not. Records indicate that accidental discharges were common among the troops, who it is important to remember were more familiar with the other breechloading actions than the bolt action. Ultimately the US military adopted the Springfield Model of 1870 Trapdoor as their standard arm, and it was not until the 1890s and the adoption of the Springfield Krag rifle that a bolt action became standard.

See more pictures on our on our listing for the Model 1871 Ward-Burton Carbine.